on Potters in Print

It’s an odd time to be talking about making books. Print is moribund, publishing is underwater, media is increasingly consolidated and corporatized, and books sales are miserable. Neighborhood bookstores are endangered—and now thanks to the e-reader, perhaps even the predator responsible for their decline, the large brick-and-mortar chains themselves, could follow suit. We navigate knowledge increasingly though web-delivered bytes. Who can focus to read a book when we are wired into so many manically and magnetically engaging devices?

Even without publishing’s bleak prospects, why would a potter whose hours are largely spent in and around the studio choose to shift his attention to making a book about a historical potter, a project involving many hours—one even less remunerative then making pots—with a painfully steep learning curve, and compelling many onerous tasks comparable to some of the worst studio chores? (For me, preparing a bibliography and obtaining permissions for photographs are first cousins to scraping shelves and shipping pots.) What is the relationship between a studio life and scholarship? And why the effort of putting a printed book into the world?

Mark Hewitt and I both love books. My own pottery story shares with Mark’s a kind of romance with particular texts—many of the usual books (Leach, Cardew, Rawson, Clary Illian’s Potter’s Workbook) and some less usual ones (Watson’s Early New England Potters and Their Wares and Robert Wilson’s two Kenzan studies, for example), and also articles (in Studio Potter and Ceramics Monthly), and films such a the silent footage of Isaac Button throwing a ton of clay into pots in a single day. I grew up in New York City where books seemed to be read everywhere by all sorts of people—notably by straphangers on the subway in my commute to school. Books were central. Perhaps because both Mark and I both came to clay from outside the academy (we each came to critical thinking through an undergraduate humanities background and to clay through practical learning), the passion for books stands in for a community of knowledge that being part of a university department might represent. Great ceramic books always encouraged and inspired me to figure out how and to continue to make pots.

I had known of Karen Karnes from almost the beginning of my interest in clay. While I was pretty ignorant of the American ceramic scene of the late 60s when I began to get into clay, I was somehow aware of Karnes and her iconic salt-glazed jars. For me she was an authentic artist who had attained both a technical mastery and compelling language of personal expression, a feat even now, but absolutely majestic seen from my seventh-grade ceramics room. A dozen years on, as I was becoming a professional potter, I met Karnes and later participated in the show she has curated for the last 36 years at the Art School at Old Church in New Jersey. As I got to know more about Karen’s work and her fascinating story I began thinking about writing something about her.

In spite of Karnes’s status as a doyenne of studio pottery, she had had no major publication or museum retrospective (though there had been many articles about her over her long career, and an excellent short retrospective catalogue that her then-dealer Garth Clark produced in 2002). My preliminary research led me to contact the Smithsonian Archives of American Art to get a copy of a 1986 interview in their collection. As it turned out, they wanted to do a second interview and in 2005 I interviewed Karen for them. A book about her was beginning to take shape in my imagination and I wanted to make it happen while she could still participate, point to sources, correct the record, and enjoy the honor. A Chosen Path was published by University of North Carolina Press last fall—five years after I’d embarked on the project. The book accompanies a major retrospective curated by Peter Held of the Arizona State University (ASU) Ceramics Research Center, who became my partner in this project. The primary funding for the publication was part of the larger grant that supported the retrospective exhibition, which is traveling to five museums.

Documenting Karnes’s career was complicated by the 1998 fire that destroyed her home and studio, consuming all her sketchbooks, records, and photographs and limiting the extant archival material. And, too, there was Karnes’s famous reticence: she prefers to let the work speak for itself and rarely talks about her creative motivation, intentions, and process. We are left with her pots, the accounts of her living associates, materials preserved by various individuals and collections, and her remarkable biography.

I wanted to make the argument that great pottery—like all great art—reflects, includes, and reshapes the wider culture in which it is created. What came together in Karen’s life—communitarian living experiments and the grappling with community and privacy, the simultaneous embrace of tradition and modernity, the fusion of Asian aesthetics with European modernism—were manifold cultural forces which, filtered through her original vision, have helped define not just contemporary studio pottery but the wider American culture. These themes are explored in a series of essays I commissioned from writers in and outside the field; I wanted the book to engage not only the ceramics community but general readers as well. Karnes is a good subject for such an undertaking because her life intersects with so many critical moments in American creative culture: in New York City at the High School of Music & Art in the 30s and Brooklyn College in the 40s, at Black Mountain College during the avant-garde experimentation of the early 50s, and at the Gate Hill Cooperative creative community with other Black Mountain refugees, including her former husband ceramic sculptor David Weinrib, MC Richards, John Cage, David Tudor, and their patron, architect Paul Williams and his wife, the author and illustrator Vera B. Williams. The book includes over 60 archival photos and related materials that I gathered and digitally restored as well as images of the 70 works in the traveling retrospective. My intention was to provide plenty of history, context, archival material, and diversity of perspectives and voices from multiple writers.

Garth Clark, the preeminent scholar and Karnes’s former dealer, opens the book with a foreword that sets the tone for the project, placing Karnes squarely within twentieth-century modernism. Chris Benfey, an interdisciplinary scholar who writes about figures and movements in American art and culture in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, expands Clark’s argument in the volume’s lead essay. Invoking Longfellow and Willa Cather, Benfey connects Karnes’s experience to the sweep of American arts from the communitarian utopias of New England transcendentalists, to faculty debates at Black Mountain College over the need for makers in an environment driven by ideas, and to the back story of the legendary Hamada, Leach, and Yanagi 1952 seminar there.

Although Karnes never particularly identified herself as a feminist, she came of age as an artist at the same time as second-wave feminism, and her career reflects many of the opportunities that were emerging as women expanded their self-definitions and reorganized sexual politics. Raising her son as a single mother, independently winning the bread as an unaffiliated, entrepreneurial maker, and eventually forming a life partnership with the Welsh educator and artist Ann Stannard marked Karnes as a trailblazer, inspiring her peers and many younger women potters along the way. Jody Clowes, a curator at the University of Wisconsin, explores these themes in her essay, along with Karnes’s working-class Jewish leftist roots.

Karnes’s career brackets the golden years of the American craft movement, beginning with her studies under the charismatic Chechen-born modernist designer and architect Serge Chermayeff at Brooklyn College right after the war, and leading to a stay in Italy where she lived in a ceramics manufacturing town and met the prominent designer and publisher Gio Ponti. After a year at Alfred on a fellowship (where, not intending to teach, she declined to finish her MFA) she went with Wienrib to Black Mountain College in its heyday when so many New York School painters passed through. John Cage and Merce Cunningham’s first “happening” took place, as well as the famous summer sessions, first with Soetsu Yanagi, Bernard Leach, and Shoji Hamada (and Marguerite Wildenhain), and the following year with Peter Voulkos, Warren Mackenzie, and Dan Rhodes. From almost the beginning of her career Karnes began showing at American House, the American Craft Council’s New York gallery, and won prestigious awards at the Syracuse (later the Everson) national shows. Karnes’s role in the postwar craft movement and her intersection with the culture of the time, is brought forth by Janet Koplos, who has chronicled more of this history than perhaps any other writer.

Edward Lebow meditates on the pots themselves in his essay. His analytical eye illuminates the suggestive dualities in her work. Resistant to literal definition, he finds more evocative mergings of multiple polarities: inside/outside, landscape/body, male/female, spiritual/physical.

These essays are bracketed by my own introduction to the book and by Karen’s narrative, which shows her lively ironic wit and down-to-earth sensibility; a more personal encounter with the artist.

There’s a summary of the book—but what about its making? How does that fit with life in the studio? Bringing a manuscript of this sort to press is very expensive in terms of time, labor, and money, and its inflexible deadlines, and binge-like periods of intensive demand have a huge impact on studio and family life.

We had to raise about $75,000 for the publication (including, printing, design and layout, photography, and writer’s fees). ASU, the grant administrating institution, will receive royalties, but they will be a drop in the bucket at best. Working with a prestigious academic press such as the University of North Carolina provides the infrastructure of distribution and publicity, peer review (a double-edged sword), editorial and design support, and printing channels—but none of this pays a potter’s bills.

As for time and labor: let’s leave that to W.B. Yeats:

A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.

Better go down upon your marrow-bones

And scrub a kitchen pavement, or break stones...

Of course, Yeats is talking about writing poetry, but all writing—as was brought home in working on my introduction—is exquisite torture. Meeting the deadlines (and persuading everyone else to do so), satisfying two peer reviewers, and coordinating multiple essays to create a seamless whole—the entire making of a book—is a long and arduous task. “Laborious stitching and unstitching” seems apt.

How has this project affected my own studio practice? It’s probably too soon to tell. In the studio, the hand seems to lead the well-known triad of heart, hand, and mind. Working with words, the balance perhaps tilts toward mind. Of course, without heartfelt engagement the triangle collapses altogether, whatever its tilt. It was thrilling to work with primary documents, discover photos, interview Karen’s associates, and find materials in the Black Mountain Archives, such as letters between college president and poet Charles Olsen and Bernard Leach negotiating his workshop fee, or the original letter from Charles Harder at Alfred recommending Karen and David Weinrib to the college. “Karen has a placid and calm disposition and is a most attractive personality. She can be depended upon to keep the team on a practical course…” Seeing Weinrib’s annotated drawing of the tent they lived in in Pennsylvania in 1950 or a 1968 photo of Karen’s studio desk with pots made at Black Mountain by Hamada and Voulkos, made vivid for me a particular historical moment, the struggle and achievement of a particular life. Seeing these artifacts, which speak to her courage, her consistent creative growth, and her independence strengthened me.

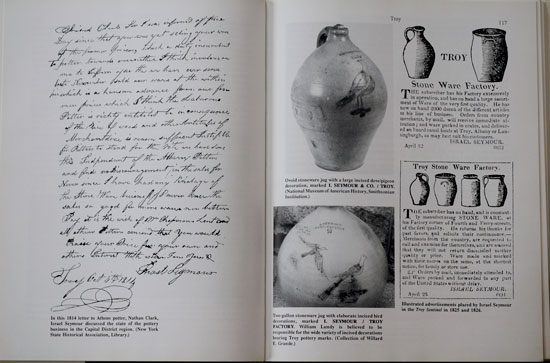

One way to understand who we are as contemporary makers and imagine how we might move forward is by deepening our knowledge of history, feeling ourselves to be part of it. My work in the studio has always been fueled by an engagement with history. I have made a hobby of studying the salt-glaze potters who worked in the Northeast of the United States during the nineteenth century ever since I stumbled on an 1854, locally-marked sherd on my western Massachusetts property. We work in an environment that has evolved out of the cultural forces and work of generations of makers that came before us, whether they be nineteenth-century American jug-makers or pioneer studio potters. Making A Chosen Path was working with clay in a different way than on the wheel and in the kiln. I was working out how a key predecessor developed her creative vision within the circumstances of her own time. The book is an attempt to contribute to the knowledge that underpins my studio practice and a modest gesture to repay the debt I owe those who came before.